I went to Thailand for the first time in 2012 to teach English on a six-month contract in a public high school two hours northeast of Bangkok. I came home after my first ten months because of a family emergency and returned in April 2014. In September 2015, I moved to Spain. I’ve been living here since then (going on my third year).

So if you total that up, my “gap year ” (rather my “gap” half a year) turned into, yep, five years abroad (going on six).

This is about why and how that came to be. But first, can we talk about the phrase “gap year”?

On the ” gap year “

What does it even mean? What, exactly, are we taking a “gap” from? Over the years, I’ve heard many of my English-teaching peers abroad say that when they get back to the “real world” they’re not sure they’re going to get a “real job.”

I think this term and the way we use it diminishes both the experience of what travel, living, and working abroad is, and it diminishes the communities we are spending our “gap” year in. Perhaps inferring that these communities and the time we spent there are something we squeeze into our “real” life because, well, our time there is temporary.

But what happens when you actually do get attached? What happens when you make connections in the communities you’re in and learn that you can actually contribute to them in more meaningful ways than what a short, fun-filled year can give you?

So perhaps a “gap” year should just be called and thought of as another year of education. Because that’s really what it is.

Why Six Months Became Five Years

I learned to reevaluate what I truly value.

Living within cultures that are not my own taught me to see the way other people live. After living among people who live a certain way for months, and then for years, it becomes difficult not to adopt those ways.

I’ve been fortunate to live within cultures where life moves a little more slowly, where work isn’t the first priority, and working all the hours of the day isn’t valued as much as time with people you love.

Yes, it took me miles of distance and time to learn how much I truly value my family, my friends back home, and myself, really. Slowing down and finding empty spaces in my day where I can choose what to do instead of crunching out work all day has been most freeing.

It gave me insight on my own culture(s).

Living and working abroad has helped me see the United States from the perspective of those I live among. From the perspective of my students, of my fellow teachers, of my friends who are not American. Sometimes that view is critical. Sometimes that view is in awe. Sometimes that view is that American culture is a strange and uncontrollable beast.

I also grew up with Filipino parents, and many people have been confused by this. Being brown and in Thailand, some people thought I was Thai. Often my interactions with vendors or van drivers or cafe owners were explaining the trajectory of how I obtained a) the color of my skin and b) that blue passport.

This has helped me see my own privilege, as a citizen of the US, as someone who comes from a rich cultural heritage, and as someone who lives between the two.

Learning languages stuck.

My first six months in Thailand, it seemed like I was never going to learn Thai. And I still haven’t learned it to the best of my ability or to the extent that I think I should have. But I learned that living immersed in another language helps me see things the way others see them. It shifts my perspective every time I have to communicate through another system of thought.

Living in another language taps into other parts of me that are harder for me to reach while speaking English. When I speak English, it’s mostly about my ego. It is, after all, my job. I’m much more vulnerable in the languages I’m learning, mostly because I’m not as confident or as capable in them as I am in English. This allows me to think more compassionately. This is the way I prefer to live.

It got difficult to leave.

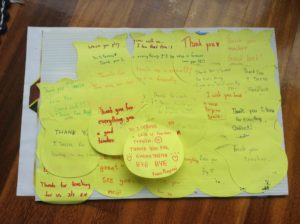

After two years in Thailand, I started to feel a part of the community. Though I know in all truths that might never be the case. But I think I did make true connections. With my fellow teachers, with my friends, with my students. We send each other messages on our birthdays. They ask me to come back. And I miss them. Sometimes almost as much as my own family. Because, at least for a few of them, I felt as if that is what they are.

Now in Spain, I have my partner. And his family is here. So it’s getting difficult to leave here, too. But at least this time, I can take my family with me.